Whenever I see the words ‘forwarded many times’ blinking up at me from the bottom of a WhatsApp from my mother, I want to banish her to the naughty step so she can THINK about what she’s DONE. Then I regain some sense of self-control and sweetly ask her to please fact-check her sources before hurling more petrol-infused logs onto the burning pyre of human understanding.

Not to be too dramatic or anything.

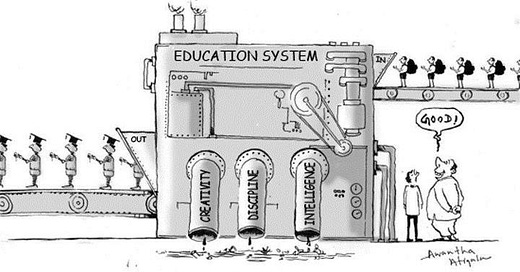

How the school system encourages conformity

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not blaming my mother (promise, Mum). We were literally educated to accept the information presented to us without questioning it. You must remember Teacher of the Year, Miss Trunchbull, spitting the words: “I'm right and you're wrong, I'm big and you're small, and there's nothing you can do about it,” into Matilda’s unassuming, timid little face. It sounds extreme, but isn’t this what we implicitly teach every kid at school?

Think you’ve written a beautiful haiku? Not so fast. Let the report card tell you what you’re worth.

On the cusp of nailing the quadratic education? BRRRING BRRRING. Oops, time’s up. Guess it’s not that important after all.

Want to learn about the opioid crisis? Stay put. Remember what I told you, child: you’re only as curious as all the other 12-year-olds.

In so many ways, school is priming kids to not only conform, but to become dependent on authority figures to classify their worth. From their early years, we prize conformity over curiosity, draining a child of their natural ability to question the world and reason independently.

In his globally recognised TED Talk, Sir Ken Robinson makes a similar argument, claiming that schools kill creativity. Sir Ken has certainly received his fair share of backlash from educators who believe structure and discipline are key to unlocking creativity and enabling pupils (especially those who are less advantaged) to thrive. I don’t disagree with them. But you need a healthy mix of structure and chaos to unleash true creativity. And quite frankly, Sir Ken didn’t have it all wrong.

When you dig into the origins of the system, you discover a cold, hard truth. It’s all deliberate.

The modern schooling system was designed to create conformity.

About 150 years ago, conformity was the most valuable thing to society. In the early 19th century, the transition from an agricultural society to an industrial economy required a reliable way to scale the production of goods. Enter the factory line. It made sense to mirror the approach and apply it to schooling, particularly at a time when religious tension between Protestants and Catholics divided public life. The godfather of modern education wanted to uphold a sense of common national identity. Chairs and tables were set up in punitively straight rows; a teacher was planted at the front; children marched obediently from class to conveyor bel-I mean class–at the shriek of a bell. Let me jog your memory:

I’m not saying the system didn’t serve its purpose. It’s simply that the world continued to evolve as the factory line remained static (for the purposes of this piece, I’ve radically simplified this history. If you’re interested in an alternative perspective, this is a powerful rebuttal to the popular ‘factory line’ history of education).

The true travesty is that whilst technology and access to information accelerate at an exponential rate, we are still pumping out cookie cutter clones fit for a mechanical, industrial workforce. Such an outcome doesn’t do justice to the sheer sense of wonder and inherent creativity with which kids start school (something they share with society’s greatest thinkers, by the way).

The problem worsens when school leavers enter the real world. Like the homework they used to tuck diligently into their schoolbags every morning, young adults unwittingly package this conformity and intellectual dependence into their briefcases as they set out into the working world. Except this time–instead of being drip-fed carefully curated information–digital natives are now swept up in a chaotic whirlwind of never-ending knowledge.

They are completely unprepared to deal with this reality.

Modern media doesn’t want us to think

The Internet has massively accelerated the rate at which ideas are spread. As Martin Gurri wrote in Revolt of the Public: “More information was generated in 2001 than in all the previous existence of our species on earth. In fact, 2001 doubled the previous total. And 2002 doubled the amount present in 2001, adding around 23 “exabytes” of new information—roughly the equivalent of 140,000 Library of Congress collections.”

The evolution of the media to social media has prompted the permissionless creation of content and so-called thought leadership. In a world of information abundance, media platforms are locked in a zero-sum competition for reddened eyeballs and frantic clicks. It’s within their interest to design emotional hooks and headlines that demand our attention, fuelling the negativity bias that warps our perception of reality. As one of my former colleagues put it, social media is like standing in an office with 50 rooms and having 50 people scream your name all at once, demanding your attention RIGHT NOW PLEASE.

Once you factor in the commercial incentives that govern the world of media, things get really messy. People pay for certain publications because they believe they will unlock access to higher-quality journalism. This makes them feel good about themselves because they’re not just informed like the masses, they’re well-informed. The thing is, paywalled publications reinforce our perspective, because most of us only pay for information we agree with. Why should I give someone my hard-earned money to challenge my entire worldview? Uh, no thanks. I’ll take some velvet-adorned cushions for my echo chamber, please and thank you.

The slightly inconvenient truth, therefore, is that it’s not the media’s role to present the world as it really is. Quite the opposite in fact. It’s the media’s role to present the world exactly as we wish to see it.

As Hans Rosling, the author of Factfulness rightly says:

“It is upon us consumers to realize that news is not very useful for understanding the world.”

How are we meant to cope with this mind-boggling combination of information overload and twisted incentives?

We have our ancestors to thank

Well, we’re forced to create a filtering mechanism for ourselves. In a world of chaos, we need order. To extend my colleague’s analogy, I can’t possibly converse with Priya in Room 49 whilst listening to Rich in Room 13 and absorbing what Jo in Room 32 is saying, all at the same time. I have to choose. And I have to choose quickly, because the next tidbit of information is a mere swipe away and I simply must have an opinion, lest I appear uninformed!

So instead of independently forming our own thoughts, we default to lazy thinking. We box up the opinions of others, label them ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ (which–don’t forget–is completely arbitrary, because our information diet just reinforces our existing beliefs) and start spewing them as if we’re the undisputed intellectual authority. In our defence, our minds did not evolve to become truth-seeking machines; they evolved to analyse limited data points and prioritise the opinions and information that helped us survive.

Just as you’d want to be affiliated with the strongest hunter-gatherer in the tribe because he would keep you safe from harm, or associated with the tribeswoman with the widest hips because she’d give your offspring the greatest chance of survival, you adopt the opinions of the people who further your self-serving narrative. And when we choose once, we’ve chosen forever. Turns out our brains do this weird thing where if Person A says something we believe is true and Person B says something we believe is false, the next time we don’t know something, we’re more likely to believe what Person A says, than Person B. Except we don’t just adopt these views. We imitate them whilst deceiving ourselves that they’re our own.

And then suddenly we become the experts. As a kid, I was unaware that you could become an expert in anything overnight. Now, being qualified to talk about something seems as easy as putting on two matching socks (which–ironically–is something I find quite difficult).

We’re only engaging with one end of the intellectual spectrum.

So my worry with all this is that most of us–through no fault of our own–have forgotten how to think. The combination of our conformist schooling system, the toxic traits of our information-rich society, and our own cognitive biases mean that we’re often restricting ourselves to one end of the intellectual spectrum.

In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald said:

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

It’s funny in a way. You’d expect that there would be a strong positive correlation between the amount of information available to us and our ability to come up with novel insights about the world. In fact, David Perell’s Paradox of Abundance claims that the median consumer is worse off, being pulled in all directions by the media’s gasp-inducing clickbait, whilst it’s only the minority who are able to see through this abundance, connect the dots and form novel insights.

It’s never been more difficult to do this. It’s also never been more important. In a world where we’re faced with truly global, interdisciplinary challenges, people who are able to reason independently and openly discuss inconvenient truths are like diamonds in the rough.

Rare to come by. Formed under immense pressure. Immensely valuable.

WhatsApp actually makes it quite hard to forward a message. It takes 5 taps. So the next time you receive one*,* maybe don’t banish the sender to the naughty step, but at least consider all the factors that led to them making that very intentional choice.

Resources & Inspiration

Dumbing Us Down by John Taylor Gatto

The Secrets of Our Success by Joseph Henrich

On Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory

Paradox of Abundance by David Perell

How Philosophers Think by David Perell

Factfulness by Hans Rosling

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

What Sir Ken Got Wrong Pragmatic Reform

Revolt of the Public by Martin Gurri

The Invented History of 'The Factory Model of Education' by Audrey Watters