on omakase, or: the hidden flow state between artist and observer

what omakase, csikszentmihaly, and weedy seadragons have in common

Dusk flung a scarf of darkness across the entrance of the unassuming izakaya. The owner glanced up at us, surprise illuminating the crow’s feet that betrayed a lifetime of laughter. “Futari desu onegaishimasu?” we asked hesitantly.“Hai, hai!” the owner exclaimed, shuffling towards us and gesturing to two counter seats in front of his workspace. As we settled in, our host typed a simple question into Google Translate—“Anything you don’t eat?”—before placing a mysterious phone call.

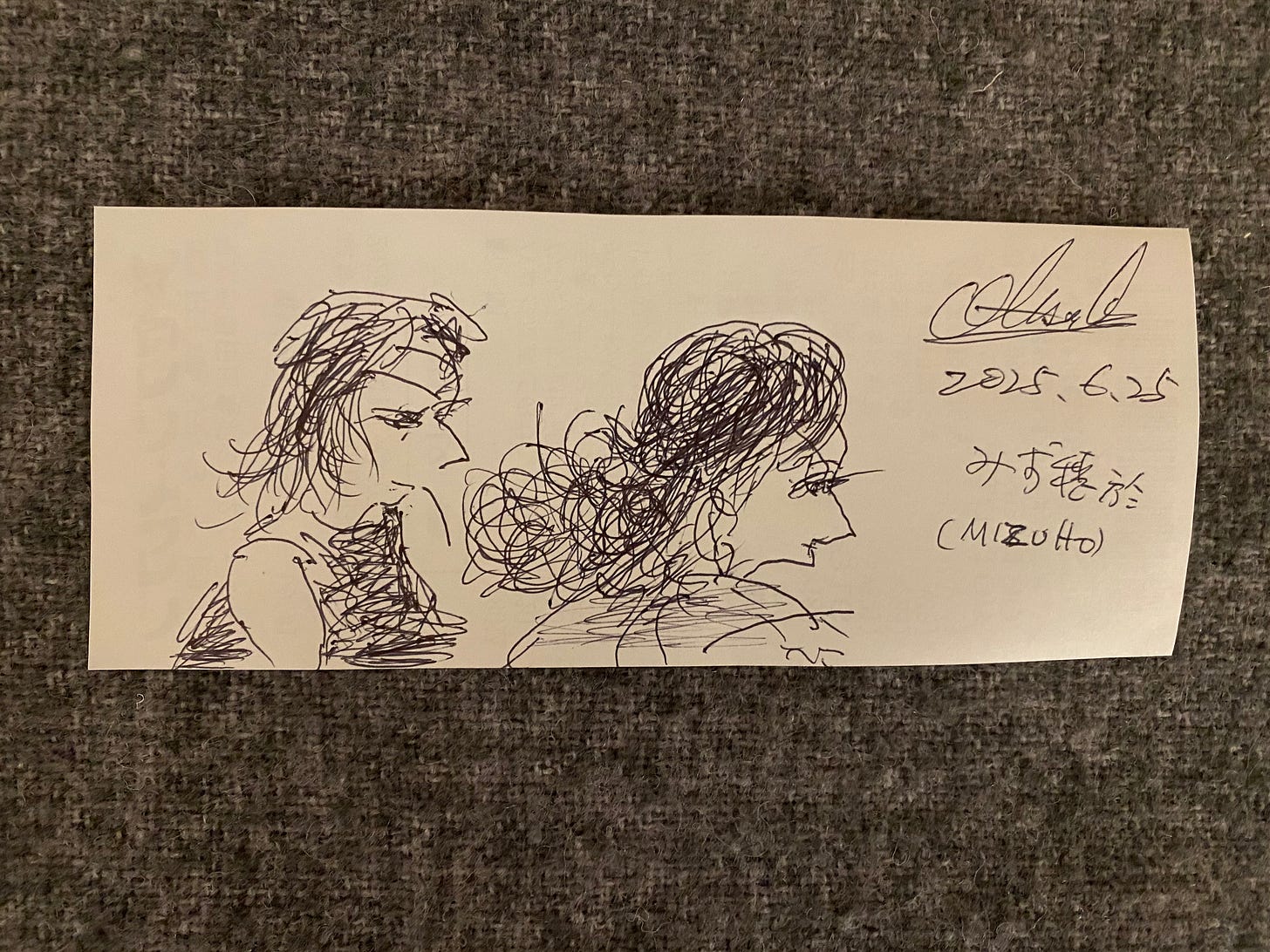

A minute later, an elderly woman pushed aside the curtain and began fussing over us as if we were her long-lost grandchildren. “Where are you from?” she asked shyly in broken English, as she picked up a rock of Himalayan salt that had travelled over 11 days from Machu Picchu–as was kindly translated by the only other customer, who surprised us with a hyper-realistic portrait of us enjoying our meal–and casually started grating it. We beamed, responding with our broken Japanese, as her husband began pulling out edamame, tofu, aubergines, courgettes, mushrooms, and sweet potatoes from his infinite stores. And thus the fire was lit. Over five courses of the homely yet heavenly food that only nonnas and nanis can cook, our evening faded into a subtitled musical, the vegetable spotlit as its leading lady.

As I’ve ventured and dined across Japan over the past two months, the uniqueness of the omakase お任せ experience has struck me time and again. Roughly translating to “I’ll leave the details to you”, omakase originated in sushi joints in the 1990s, before being adopted by other Japanese and Western restaurants. As opposed to ordering from the menu, omakase permits the chef to make choices about what to serve you. Dining out becomes less of a transaction with faceless staff hidden by a steel door, behind which stark lights lay bare the tyranny of the head chef. Instead, the chef works like an artist, performing her craft to the delight of her audience while developing a trusted relationship with them, adapting the palette from which she paints their plates.

But I soon realised that omakase is more than just “chef’s choice”. Buried like a pearl within this word is a profound intimacy: it derives from the verb makaseru 任せる–“to trust”. This depth of trust between artist and observer is rare in and of itself. Imagine telling your local bookseller with a nonchalant wave of the hand: “Omakase. I don’t need to read the blurb. I’ll buy whatever you recommend.” Or, more impressive still, entrusting the architect responsible for your home renovation: “Omakase. I trust you and your understanding of what I want. Go forth and design.” The thing about trust is that, much like love, it is a verb, not a noun. To surrender one’s agency–trusting that the unspoken decisions of a perfect stranger will not disappoint you–is to knead a new connection with the dust of intimacy.

Whether at a famed okonomiyaki spot in Osaka, where the chef reminisces with old friends while welcoming new customers, or at a low-lit Italian restaurant in Tokyo, where three chefs waltz around each other, as if laced together like flowers on a daisy chain, each omakase holds a singular magic. This magic arises not only from the trust between the chef and her customer. It arises when the chef trusts her craft as much as the customer trusts his taste.

Any dance between artist and observer is beautiful to behold, but when both trust themselves, a mirror materialises between them. Both know that their actions matter, as if the person in the mirror is playing to the rhythm of their softest sigh and their deepest breath. If you have ever played the improv game where you mirror someone else’s actions down to the metronome of their blink, you will have experienced the vulnerability of this reflective dance.

I believe this is a type of flow state. Csikszentmihaly’s Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience brought the concept of flow into the mainstream in 1990, around the same time omakase was gaining steam in Japan. The flow state is one in which the demands of the situation slightly exceed your current skill level. If you are too skilled for the demands of the task at hand, you fall into the trough of boredom, while if the demands of the task overpower your skills, the blade of anxiety grazes your confidence. The flow state rests on a knife edge.

When bands or sports teams feel their selves ending and their egos blending, it is known as group flow. Members of such groups have described a transcendental quality to group flow, as if they become a conduit for a force outside of themselves. Observers sense this too. We feel, rather than hear, the discordant note that accentuates the jazz band’s harmony. We feel, rather than see, the stillness that spotlights the synchronicity of the dance troupe’s routine.

Scholars have said that the amount of time you spend in flow state is correlated with how meaningful you find your life. Little research, however, has investigated the type of flow experienced in settings like omakase, where two people are perfect strangers, rather than on the same side working towards an explicit goal. In omakase, the pulse of trust between the actions of one and the feedback of the other accelerates the smudging of egos. The flow that emerges reminds me of the dance of courtship that weedy seadragons perform (please watch it; it’s wonderfully calming, and I was delighted to have a relevant enough excuse to include this link).

The lucky few of us spend many hours a week in flow, dedicated to work we love. Those who don’t experience flow at work may experience group flow in their personal lives. But the omakase flow is particularly rare. It is the dissolution of the stranger’s ego that creates space for unexpected connection. Outside of the izakaya, what beauty might unfold when, instead of shrugging off the opinion of a stranger, two future friends say I trust you and I trust myself? The magic, it seems, lies in the spaces between us. Perhaps the most meaningful experiences, much like the most memorable meals, come not from making an order, but from trusting someone else to surprise us with exactly what we need.

Thank you to my dearest Hanne Peeraer, Milly Tamati and Anoushka Khandwala for reading drafts and offering feedback on this piece.

Beautiful concept and exploration of it, thank you! I recently read a comment from someone somewhere that “when I rate a book 5/5 it’s not because I think it’s the best book ever written, but because it’s exactly what I needed to read in that moment.” I think it swims in the same waters as this, and perhaps as writers we’re equally trusting that the right person will find our words at the right time. I’m continuously realising that we’re all just in a constant game of push and pull, and as you say, trust is one of the most important sensibilities in extracting joy, meaning and connection from as many moments as we can.

I love the concept of that word. A few of my friends have expressed that they really like Japan for the culture and their values and their humanity. I haven’t experienced that first hand. But in England I’ve experienced that people think you’re stupid if you trust a stranger to do something.